Tl;dr This post explores the alarming potential for exclusive order flow to render the builder market uncompetitive. A lack of competition in the builder market threatens to cause rent extraction, poor user experience, and entrenchment of builders with undue influence over network incentives. While cause for concern, the negative externalities of exclusive order flow can be mitigated or wholly avoided as presented in a series of articles, of which this article is the first.

The gist of this article is captured in a talk delivered at the MEV Workshop at SBC ‘22. For discussions on this post, see here.

Introduction

What is order flow?#

In the context of Ethereum, we regard anything that allows one to change the state of the blockchain as an “order.” The canonical example is a transaction like the ones found in the mempool, although the concept extends to other formats like “intents” from account abstraction too. I refer to collections of orders as “order flow” (OF) and refer to exclusive access to order flow as “exclusive order flow” (EOF). As you will soon see, EOF will be the main antogonist in this article, primarily because most forms of exclusivity easily prevent competition, which is necessary to have a “good” MEV market.

A good MEV market#

The particular MEV market in question in this article is PBS in the form of MEV-Boost, but many different forms of MEV markets likely succumb to similar descriptions and dangers. In order to argue that EOF can have undesirable effects on the MEV market, it is important to first establish some of the properties we require from PBS:

- (Approximately) dominant strategy for proposers: This is the most essential aim of PBS, so hopefully you are already familiar with this idea. At a high level, the aim is that either the proposer’s best strategy is to build blocks through the builder market or their best strategy yields only marginally higher returns than what the builder market has to offer. We have this goal to prevent centralisation of stake on Ethereum.

- No rent-seeking: The majority of the MEV that is extracted should not remain with the extracting parties (searchers/builders), but should rather flow back to the rest of the ecosystem. Where exactly the value should flow is a topic for another article, but the obvious contenders are validators, users and DApps.

- Censorship resistance: just like before PBS, a valid order should be included eventually and, ideally, without much delay.

- Improvements to UX: admittedly this is more of a desired than a required feature. However, given the addition of a sophisticated agent to the Ethereum ecosystem, it seems remiss not to leverage this agent for improvements to areas of the ecosystem we know to be weak. More detail is added to what UX improvements are possible.

Where the orders flow#

Consider a wallet trying to send exclusive order flow to a single builder. In order for the wallet’s orders to be executed the builder who receives the orders must land a block on chain, which may not happen immediately. End users don’t like delays and delays also make things like gas fee estimation a lot harder so the wallet is incentivised to minimise this delay by sending OF to the builder with the highest inclusion rate, further increasing their dominance of the market. Clearly, this is a centralising force on the builder market.

There are various reasons why a wallet might do this. The most obvious is contractual payment for order flow from the builder, but it might also be in exchange for certain features from the builder or because the wallet maintainer is too lazy to integrate with any builder apart from the largest, dominant builder that produces most blocks anyway. These motives and the ability to control order flow are not unique to wallets. For instance, DApp UI’s are in a very similar position. Lets call an agent that could play this role an “originator” for generality.

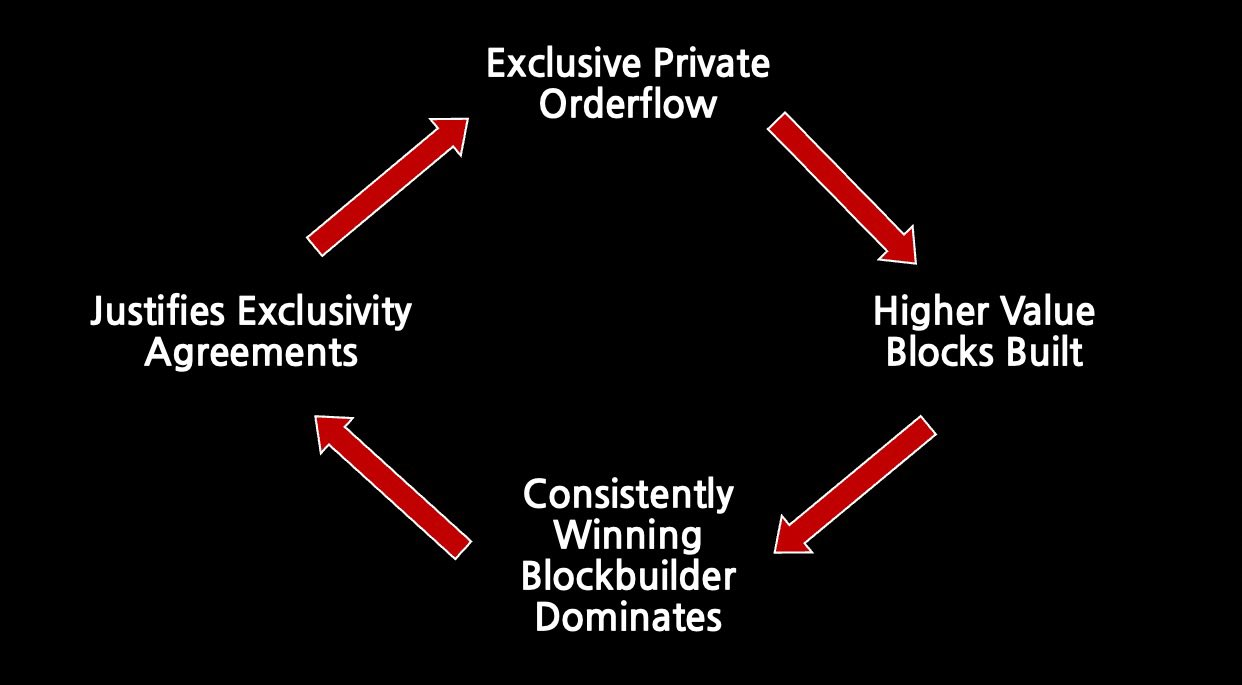

Diagram creds: Jon Charbonneau

The problem

Exclusive order flow would allow a builder - or small group of colluding builders - to capture the builder market, making it effectively uncompetitive. As we will see, this would have significantly negative consequences on the builder market.

Capturing the market#

Consider the builder market centralising to a small number of builders, as we expect it will (and we’re OK with that). In a competitive state, these builders would be spending the majority of their revenue on trying to outbid their competition. The builders could collude to drop their bids significantly and share profits, violating the property of no-rent seeking. Now consider two scenarios:

- A new builder, Bob 👷🏽♂️, enters the market. Since the bidding ring is bidding very low, it is easy for Bob to outbid them. The bidding ring could include Bob in their ring, further dividing profits, but, as more builders enter the market, the bidding ring has no choice but to lift its bids to compete, shifting value back to the ecosystem.

- Bob enters the market, but cannot access the majority of order flow, because it is all being sent directly to the incumbent builders. As a result the Bob’s blocks are not worth much in comparison to the dominant builders’ who hardly have to try to outbid Bob no matter how good Bob’s building algorithm or user features. Bob attempts to acquire order flow, but originators already have agreements with the incumbent builders. The originators are unlikely to enter similar agreements with Bob as he will likely not have a high inclusion rate. It may even be the case that wallet maintainers simply don’t feel the overhead of integrating with Bob is worth it. After all, Bob hardly gets any blocks on chain.

Hopefully, it is clear that the second scenario is the bad one as it sees the incumbent builders continue to retain the majority of MEV revenue, violating the no-rent seeking property. One may contend that the scenarios above did not take into account the payment that originators are receiving in exchange for their order flow. However, if an originator’s business model is selling EOF, switching and sending order flow to a small challenging builder would incur large latency penalties. This switching cost is likely to be reflected in the payment from incumbent builders to originators.

Additional Consequences#

UX: Access to order flow gives builders a competitive advantage. If builders weren’t able to secure payment-for order flow (PFOF), they would be incentivised to compete on implementing user features to lure OF their way. The space of potential builder features is, as of yet, largely unexplored. Some of the ideas that have been floating around include account abstraction, backrunning-as-a-service, gasless cancellations, gasless orders, pre-confirmations and state channels. If order flow does not respond to the implementation of new features because it is tied up in PFOF contracts or some other reason, there is no incentive for builders to implement these features.

It should be noted that having more order flow than another builder because of superior features is different from having more order flow because of PFOF. In the former case, the barrier to entry is implementing more features, in the latter the barrier to entry is payment and convincing originators to break contracts only to incur longer execution delays. In other words, exclusivity is not implied by features, but it is with PFOF.

Proposer incentives: Control over the majority of the value in the builder market leads to influence over proposer incentives. Consider crlists. When a proposer publishes a crlist (or performs any honest behaviour in the general case), some builders may opt not to send blocks to that proposer because they are actively censoring the listed accounts or because they are trying to disincentivise publication of crlists in general. If the market is competitive, withheld blocks should be readily replaced with blocks of similar value from non-censoring builders. If, however, there is only a very small number of builders able to produce valuable blocks and these dominant builders choose to withhold blocks, proposers are forced to choose between rational (profit-seeking) and honest behaviour. Forcing proposers to choose between being honest and earning high returns is bad in that it incentivises dishonest behaviour and worse in that dishonest stake earns higher returns and grows faster than honest stake, leading to honest proposers becoming an every smaller fraction of the network.

With rent-seeking, disincentivised censorship resistance and missed opportunities for improvements in UX, clearly exclusive order flow can have a large detrimental impact on the network.

The path forward#

We have established that control over order flow poses a significant risk to the network. How can we go about addressing the problem?

- The most obvious response is that the agents who are capable of engaging in harmful behaviour should be made aware of the dangers and held accountable. Large entities like Uniswap, Metamask and Infura control large and valuable fractions of Ethereum’s total order flow (e.g. some estimates place Infura’s share of total OF at over 70%) and could break the builder market in a finger snap. Similarly, builders who offer PFOF or special features to originators who send EOF should be called out. That being said, it is not in the spirit of blockchain to rely on agents to “do the right thing,” we should also build systems which are resistant to misbehaviour. Flashbots has spent some time thinking about ways to do this and we plan to make some of this thinking public soon in future posts in this series. In the meantime the points below should suffice as an overview of the areas for potential improvement.

- An interesting solution space is that of decentralised building. It may be possible to construct decentralised builders which would be incapable of carrying out the harmful behaviour outlined above. See Vitalik’s presentation at MEV workshop at SBC for more details.

- It is possible to build solutions which alter the incentives of agents in control of order flow. For example, providing a more efficient and less destructive way for wallets to monetise partly addresses the problem. Searchers also face a tradeoff in which they would like to maximise their chances of executing a bundle but are constrained by the threat of builders stealing their bundles. The result being that searchers may only submit bundles to a few dominant builders. This could be relieved by providing a way for searchers to easily detect bundle theft.

- Defaults are also very harmful. If the set of builders with whom originators are integrated is fixed, new builders cannot challenge incumbents and the development of new features will not be rewarded. Solutions which reduce the overhead of changing where orders flow seem to be a good mitigation strategy for this problem.

A proposed goal: in order to synthesise several of the different ways of addressing the EOF problem that have been listed above and to outline a research direction, I propose a general goal which attempts to encapsulate what has been written above:

Every order flows to every builder which supports its required features.

In other words, if an order is not being sent via the mempool because of a feature that some builder supports, that order should flow to every builder that supports the desired feature. Research going forward should aim to find a way of achieving this goal or proposing a better alternative goal.

Conclusion#

Exclusive order flow presents a threat to PBS and, by extension, can be detrimental to the health of Ethereum. More research into mechanisms which reduce risk of order flow capture is required. In the meantime, agents in the position to engage in this behaviour should be held accountable while the ecosystem at large should be made aware of this problem. Getting this right could mean entering a world of innovation on user features and order types, while getting it wrong could lead to a dystopic world of MEV capture.

Special thanks to Stephane Gosselin and Alejo Salles for helpful feedback on this article.